Cyber Security

The digital Arms Race

The invisible battle between spies and hackers – for information and power.

This story was published in National Geographic Magazine - 2020 / 09

Article by: Huib Modderkolk

This article has been translated. Read the original dutch version on www.nationalgeographic.nl

Internet is indispensable, but there is an often an invisible battle between spies and hackers – over information and power.

De Vries is on his way to Rotterdam in his navy blue Tesla when his iPhone lights up. A message from a colleague. The 56-year-old harbor master drives to the World Port Center, the nerve center of the Port of Rotterdam Authority.

There are problems at APM Terminals, he reads in the message. De Vries can’t place it immediately. Of course he knows APM, a company with a turnover of four billion euros a year. It has its own terminal on both the First and Second Maasvlakte, a mooring place where the largest container ships in the world moor. APM uses gigantic blue cranes to ensure that the containers go from the ship to the right trucks.

Barely a minute after the text message De Vries' phone rings. An employee of Maersk, owner of APM: “Nothing works anymore,” the man says. “Cameras, cranes, barriers: everything is out of order.” De Vries lets the message sink in as he enters the parking lot of the World Port Center, next to the Erasmus Bridge. He hurries into the elevator and presses the button for the nineteenth floor. Thats where the 'incident room' is located with a view over Rotterdam.

The manager tells De Vries that he can no longer admit ships because both APM terminals are down. They are barely visible from the harbor building 40 kilometers away. It is clearer on the computer screens: no shipping traffic is possible into the Europahaven. At Hoek van Holland, the sea fills with dots – each dot is a waiting ship.

De Vries looks around. An office space full of screens, telephones and laptops where fifteen people are busy on the phone. What's going on and what can he do?

A Port Authority patrol boat rushes to the Maasvlakte and customs will also have a look. On shore billions of euros worth of cargo has nowhere to go. Quickly it becomes busier on the N15, the main access road to the port. Dozens of trucks get stuck: they cannot enter the port area. In the incident room they see that three of the five Rotterdam terminals are now completely shutdown.

“Is it a power outage? Or is this an attack?” Thinks De Vries

“Will there be looting soon?” one of the office workers wonders in despair. De Vries mainly thinks about the containers that have nowhere to go. A store's summer collection can be in them, new phones or laptops. Or worse: perishable goods such as fruit and vegetables. Most stuff has to go further into Europe.

René de Vries is an experienced police officer. He has been through all kinds of incidents. Stabbing, red-handed thieves and threats. But on Tuesday, June 27, 2017, he has no idea what is happening. A fire on a ship or a leak of polluting substances is a clear defined problem. But what is happening to the port now is intangible.

Society is digitalising at a rapid pace. We pay with a smartphone, work in an 'online environment', communicate via an app. Surgery in the hospital, power from the wall socket, a train that is on time: it is all possible thanks to the computing power and expertise of computers. That offers great advantages. An email is reaches the other side of the world in no time. A passport is scanned in no time, a flight booked in a few seconds, a medical file viewed instantly. But it also poses new dangers. Dangers that often remain invisible.

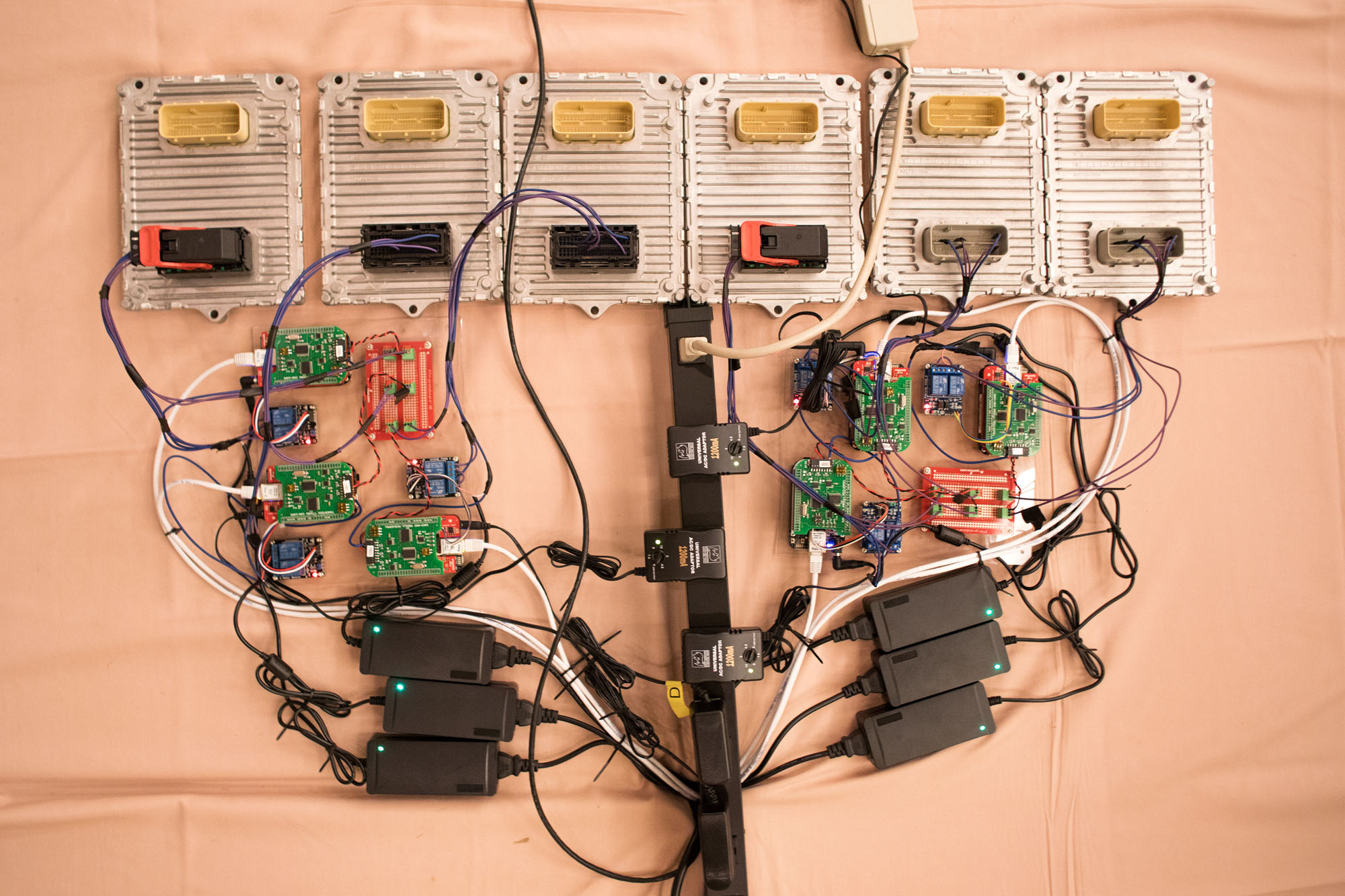

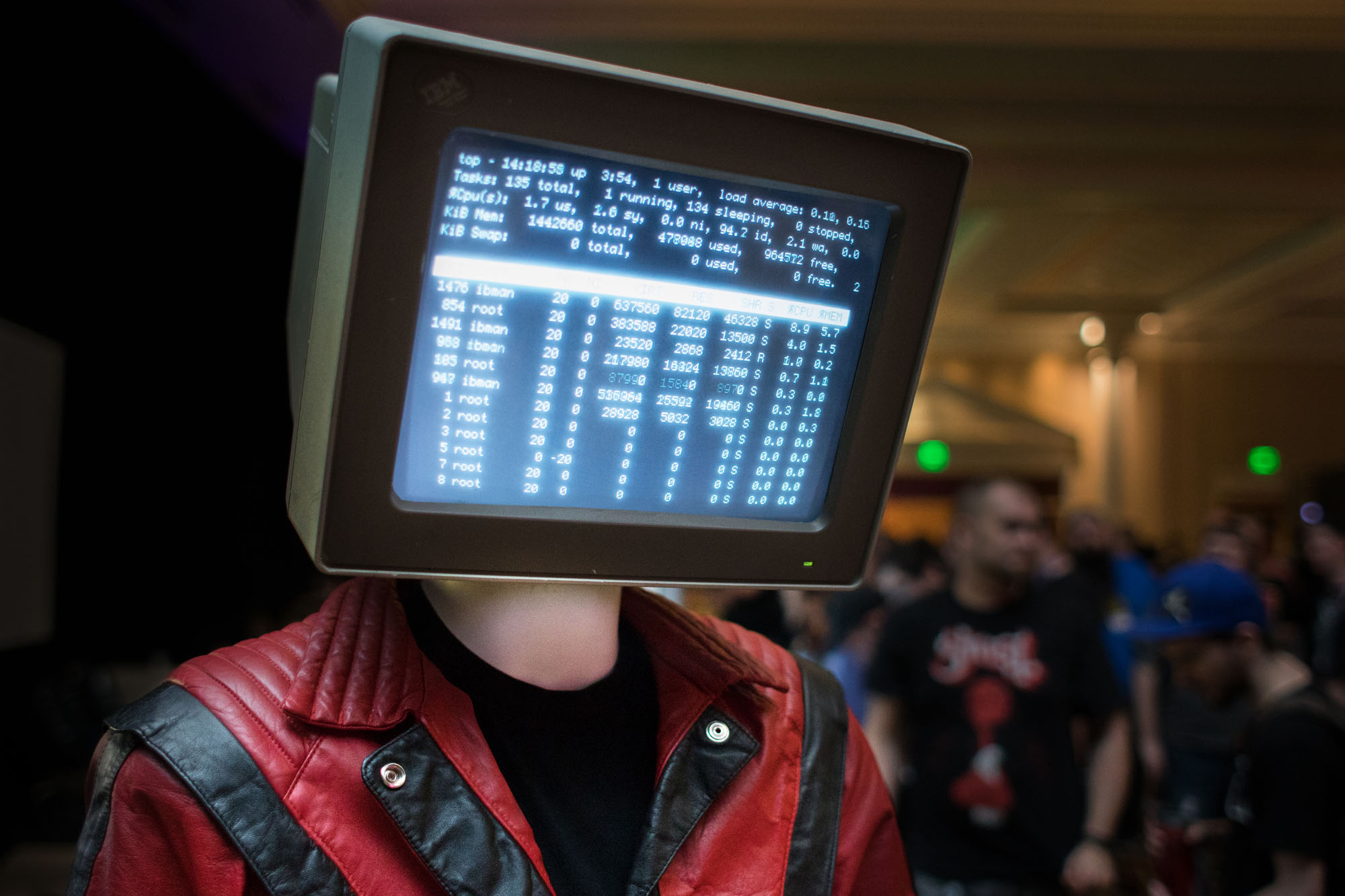

States have also discovered the digital world. They use hackers to search the internet for personal data, company data or government documents. With that stolen information states can direct the policy of other governments, influence behaviour or increase their power. Hackers are no longer the hooded boys who spend nights in a basement sitting behind their laptops and playing mischief online. They are part of the army, a criminal organisation, the intelligence service. Or they work as an 'ethical hacker' at a bank or security firm to test the network. Spies no longer have to take planes and recruit people to set up complicated operations in distant lands. Criminals move their sphere of activity beyond where they are physically located or have contacts.

In China, hackers in army uniforms sit in flats behind the computer. Rows thick, estimated to be over a hundred thousand. Every day they search for secrets in intellectual property for example in Noord-Brabant, They're constantly trying to get into ASML, or Philips. Russia sends hackers to the Olympics to hack into the Wi-F and steal data from high end guests. Thanks to fiber optic cables, they can search for information anonymously and send it back home.

To understand why digitisation makes it easier for hackers to access sensitive data this simple example: the medical file. In the past that paper file was just around the corner from the GP. That wasn’t so secure; all you needed was a standard doctor's room key to access the stack of paper files.

It also wasn’t very practical to share such medical files with other general practitioners or hospitals via fax machine.

That’s why the electronic medical record is a logical step. It’s easier to secure such an electronic file than a stack of documents in a desk drawer at a doctor's office. You can ask GPs to first enter a password and then a unique code. They no longer use a simple key lying around on a desk somewhere. The digital file can also be shared faster. GPs and hospitals throughout the country can request data via a national system. The attending physician receives sharing requests, and if the patient has given permission for the sharing of information its shared in an instant.

Safer and easier to share. But a new danger lurks around, as it turns out in 2018. When reality star Samantha de Jong ends up in the Haga Hospital in The Hague after a suicide attempt, 85 people see her medical file: hospital employees who have no 'treatment or care relationship' with her. They watch out of curiosity and can quickly access her confidential file thanks to the digital system. If these 85 employees had wanted to look at the paper file in the past, they would all have had to find the right room, the right folder and the right file. A lot more complex.

So while the security of the digital record has been improved at the front, a new risk has arisen at the back: if there is a leak, many more people will have access to confidential information. And hackers can scan for such leaks. Students with a part-time job at the Amsterdam hospital OLVG were able to browse through the medical files of all patients for years. Thousands of files of vulnerable children who received help from a youth care institute in Utrecht ended up on the street due to a mistake.

This increase in vulnerable digital data started an arms race between the secret services at the beginning of the century.

The best hackers look for the most sensitive data. Fiber optic cables are tapped, satellite communications intercepted, computer systems penetrated, laptops and mobile phones hacked.

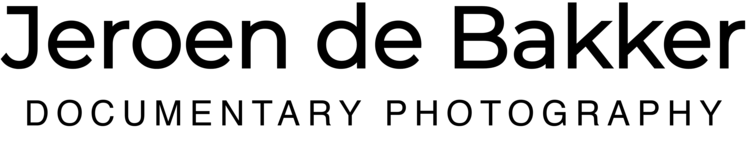

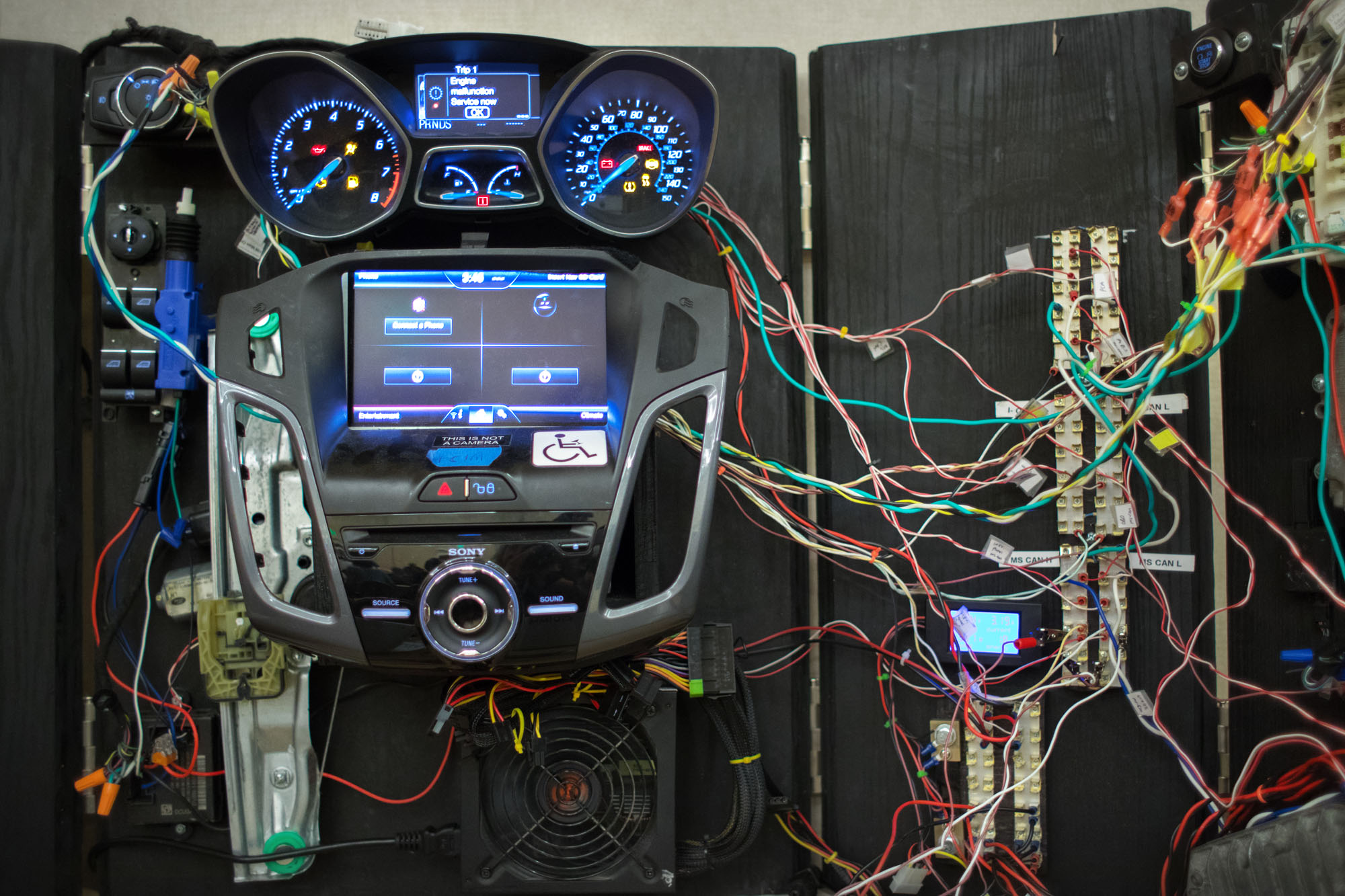

Def Con (25), the largest hacker convention in the world. In the massive venue of Ceasers Palace Las Vegas the 25.000 visitors can attend workshops ranging from lock-picking to car hacking.

The ingenuity of state hackers was shown in 2013. In a shiny building next to Brussels-North station, technical researchers found traces of malicious software. When they investigate further, they are stunned. A Belgian police investigator: 'It was all so ingenious.' A Dutch security expert says: 'This was by far the best thing I had ever seen.'

Belgacom, Belgium's main telecom provider – called Proximus since 2015 – appears to have been infiltrated by a highly professional opponent. It takes the researchers months to unravel the software and examine the 26,000 IT systems. Carefully they get a picture. They see that the attacker has left booby traps in the systems: small files that, if discovered, alert the attacker. The assault weapon moves like a many-headed snake through Belgacom's networks. It adapts to the environment and leaves eggs here and there. It is able to install itself on computers that are turned off, wait just as long for that computer to start up again and then send documents or other data from that computer without it being noticed. It can also take screenshots, copy passwords and recover deleted items on the computer.

This malware seems to be capable of anything. The researchers see that the 'snake' is most active around BICS, a very profitable part of Belgacom. BICS offers a huge data network worldwide to which hundreds of telecom companies are connected and which make connections with each other. By infiltrating BICS, the attacker can at once access the telephone and data traffic of 1,100 companies, including five hundred mobile 'operators' such as KPN and T-Mobile. And also telephone traffic from NATO, the European Commission and the European Parliament.

The investigation will last more than five years. The specialists go from one surprise to another. When they want to clean up the malware, it turns out that one day it suddenly starts to erase itself. As if the attacker knows he's been discovered.

The researchers discover that stolen data leaves the Belgacom network during the day and goes to places all over the world. A computer server in India. Or to Romania or Indonesia. From there, the data probably go to the attacker. Some servers appear to be rented with credit cards from England. But when the police take a closer look, it turns out to be prepaid cards that were bought anonymously. The police also find IP addresses that lead to Great Britain. However, London does not want to cooperate with the investigation

The Belgacom hack is the work of the best hacking services in the world: the British eavesdropping service GCHQ and the American NSA. They have unseen acces in the telecom network for more than two years. And once discovered, they destroy the evidence at lightning speed. After years of investigation, the Belgian police know that British hackers were in the network, but they can't do anything. Tracks that lead to Great Britain have been skilfully brushed away. If the British and Americans want to strike somewhere, they will. No country border or firewall will stop them.

In recent years, another development has been taking place in the digital world. And this is also noticeable in the port of Rotterdam on 27 June 2017. When harbor master Renéde Vries gets back into his Tesla late in the evening, everything is quiet and deserted. Three of the five terminals of Europe's largest seaport are not working. De Vries still doesn’t know what the cause is and this frightens him. In the days that follow, it slowly becomes clear why container ships cannot dock and cargos remain untouched.

The cause is a computer virus. Russian hackers have broken into a Ukrainian company and spread a devastating virus in Ukraine just before the national holiday. Media companies, ministries, postal companies, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant and the airport in Kiev are hit. The virus just doesn't stop at borders. The Danish Maersk also becomes infected, after which the virus quickly spreads through its networks and also affects the APM Terminals in the port of Rotterdam.

Computers that are infected immediately go black. Employees see entire departments fail. If you want to pull a network cable from a computer, it's too late: once the virus has entered, there's no stopping it. A few hours after public life in Ukraine comes to a standstill, the blue cranes of APM also come to a standstill. Containers stand motionless ashore. On the N15 towards the port, trucks are standing in a traffic jam in front of a closed barrier.

The chaos in the port of Rotterdam wasn’t caused by hackers who are looking for information, but who want to destroy something deliberately, using fiber optic cables as a weapon. Professional criminal groups use them to take companies hostage. Maastricht University, a large logistics company in North Brabant, and Royal Reesink from Apeldoorn, a distributor of agricultural machinery, among other things, each paid hundreds of thousands of euros to get their systems back. Hackers encrypted the network that good so there was no other option.

States use hackers to turn off the power at a strategic moment, disrupt air traffic, and sabotage payments. To steal emails, influence elections, spread false messages, or enter a nuclear facility with the threat of influencing its operation.

'Possible digital disruption and sabotage of the vital infrastructure is one of the biggest cyber threats to the Netherlands and its allies,' writes the General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) in its annual report for 2019. 'Several states have proven the capabilities and willingness to to use digital sabotage to achieve their geopolitical objectives.” The United States nests in the Russian electricity grid, Iran takes control of a small dam in New York, North Korea releases a virus that locks computers, after which England hospitals are paralyzed and planned surgery has to be postponed.

Western governments and also media name Russia, China, North Korea and Iran as the main culprits in this militarisation of the internet. It’s their hackers who attack at large scale. The Russians secretly try to steal documents and put them online at a strategic moment — just look at the 2016 US presidential election, when they broke into the Democratic Party board and leaked documents. Iran attacks a Saudi oil company with powerful malware and shuts it down or uses drones to sabotage oil installations.

But that's only part of the story. Because the West, including the Netherlands, is not only a victim, it is just as much a perpetrator. The AIVD is very active online. It is one of the first Western security services to recognize the threat and potential of the Internet. At the end of the 1990 the AIVD hired the first hacker. And around 2000 began the 'scraping' of the internet and the use of virtual identities started: invented persons with a fictitious digital CV who can infiltrate online. AIVD hackers already penetrated Iran's defense systems from the headquarters in Leidschendam around 2000, in search of information about the country's nuclear program.

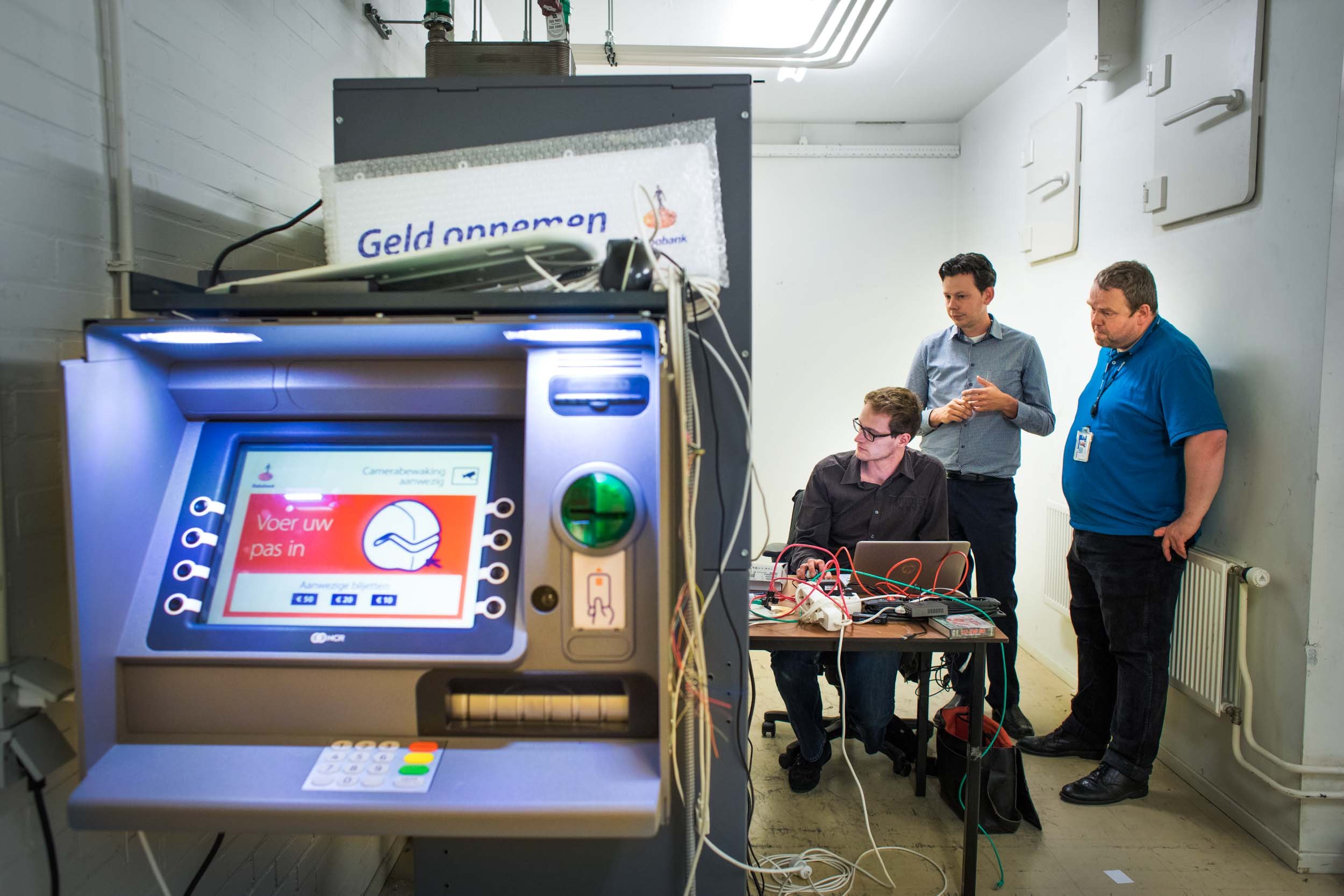

It’s no coincidence that the Dutch intelligence service hires good hackers. The Netherlands is the digital hub of the world. Several large transatlantic cables are coming ashore there connecting Europe to the US. Amsterdam is the internet hub where providers from the Middle East make a connection with major American parties such as YouTube, Facebook and Google. The Netherlands also has a very high internet density and was one of the first countries to introduce internet banking. The infrastructure is good, the taxes for large companies is low. That is why Google and Amazon like to come to the country with their data centers. That is why there are tall, windowless buildings spread across the country through which likes, retweets and video streams pass. And that is why the Netherlands has built up a serious reputation in the digital world with security company Fox-IT, the technical universities and the High Tech Crime Team of the national police.

The AIVD also leads the way in the expertise of its hackers. The service is involved in notorious sabotage actions and digital attacks. In 2007, the AIVD recruited an Iranian engineer and smuggled him into the underground nuclear complex in Natanz, Iran. This man collected information about the internal computer network and in the summer of 2007 introduces the infamous sabotage virus Stuxnet. This causes valves of the Iranian nuclear facility’s centrifuges to close, allowing more gas to flow in than intended. The centrifuges explode with a bang. It is the first time that a digital attack causes physical damage.

In 2014, hackers from the AIVD managed to enter a computer network in Russia. They end up in a building near Red Square from which Russian hackers carry out attacks. When AIVD also manage to hack a camera that is aimed at the entrance to the room, they can see which group they are in. It's Cozy Bear, a notorious Russian hacking group that constantly attacks western targets. The AIVD can monitor the Russian hackers for three years and warn the US several times if the group starts an attack.

For a relatively small organisation, the AIVD delivers an impressive performance. Sources count the Netherlands as one of the top five digitally most powerful countries, along with the US, Great Britain, Israel and Russia. In terms of expertise, the AIVD would score even better. In recent years, the number of hackers at the service have increased tenfold: from a handful to over fifty. The Joint Sigint Cyber Unit, a joint digital unit of the AIVD and the military security service MIVD, now forms the largest branch of the Dutch security services.

Now that states are increasingly arming themselves online, dilemmas are also emerging. After all, the online battle is not bound by rules. If countries use cyber units for their own gain, who will slow down the digital arms race? And can you call on other countries not to spy on you and attack digitally if you do so yourselves?

Since 2010, the race has accelerated. For example, Russia allows young Russians to pretend to be Dutch or Americans via social media, who intervene in discussions and try to increase contradicting opinions. During the corona crisis China deployed tens of thousands of accounts on Twitter and Facebook to put the blame for the origin of the virus outside of China. The World Health Organization (WHO) is under constant fire from state hackers who want more information about the coronavirus. Russian hackers try to penetrate research institutes working on a vaccine against COVID-19.

Open societies such as the Belgian and Dutch that want to protect themselves against this encounter roadblocks. To prevent unwanted influence, internet traffic must be closely monitored. That means internet freedom is declining. That emails and messages no longer just go unnoticed from one user to another. That the state is going to filter them. Look at China, which managed to censor the entire internet in the country. Words or websites that are unwelcome to the Party cannot be typed or visited.

Another dilemma is how long this arms race can be sustained. If China and Russia are constantly attacking with thousands of hackers, shouldn't the Netherlands and Belgium hit back harder? And also use more hackers? Or are you just fueling the arms race? Research by Yahoo News shows that the US CIA received secret additional hacking clearance from President Donald Trump in 2018. This makes it easier for the CIA to digitally attack and sabotage other countries. This while the United States is publicly concerned about the digital escalation and calls for "standards" in the digital domain. Norms that they themselves violate. If no country wants to be the first to step on the brakes, the escalation continues.

If these dangers are part of digitisation, why do we continue to enthusiastically embrace new technologies? Why do we keep trying to vote electronically? To create online DNA databases? Or to digitally keep track of the heart rate and sleep rhythm? The answer may be that the dangers are simply not so easy to spot. We see a smartphone, we do not see the device that records our behaviour. We see a smart meter, not the hacker who knows through the same box whether someone is taking a shower at home. We see a camera with facial recognition, but not the investigating officer who registers which street someone is walking on or the hacker who steals the database.

The battle for private information on the lifelines of the modern age takes place in invisible places. In meaningless buildings where there are racks of computers and the air conditioning blows. In cables that lie underground or at the bottom of the ocean. Behind the scenes and screens that we hold and watch every day. And as long as states and criminal hackers can move freely online and use the Internet to increase their power, that battle will intensify. Until the next electrical black out.