From Battlefield to Parliament

From Battlefield to Parliament

“The army was using guns, but the people were chopping off heads.”

By Oliver Slow

Former lieutenant-general U Hla Swe swapped the battlefield for a seat in parliament in Myanmar’s mysterious capital Nay Pyi Taw. “I must admit that it is a big challenge to move from a military government to a democratic one.”

U Hla Swe is widely known in Myanmar as Bullet Hla Swe. The 54-year old lieutenant-general turned politician blames the media for his violent nickname. “When the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) was fighting with the Myanmar army in the 90’s, we invited them to the peace process,” U Hla Swe says in his messy room in the compound for USDP parliamentarians in the capital Nay Pyi Taw. “Back then I told the media that the rebels could choose between a hand filled with gold or a hand with a bullet, but the newspapers misquoted me saying that the only way to negotiate with the rebels is with bullets.” Nevertheless, U Hla Swe wears his nickname with pride. He recently published a book titled Bullet Hla Swe’s posts for Facebook, and the back cover has an image of a bullet resting on the palm of his hand.

In his role as a politician for the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) in the upper house, the Amyotha Hluttaw, U Hla Swe insists that Myanmar cannot solve its problems with rebel groups through violence. “I know this because I am former lieutenant-general,” he says proudly. “Negotiation is crucial to obtain peace. And peace is what we want, what I want.”

U Hla Swe was born into a military family in Kyaukse, Mandalay Region, in 1960. He joined the Tatmadaw, the army, straight out of high school in 1978. Most of his 35 years of service with the Tatmadaw was spent fighting armed ethnic groups in border areas. “I was always in the field, fighting the rebels. If there were rebels, I would go.” While fighting he suffered bullet wounds in his arm and leg. The scar on his right forearm could be mistaken for a cigarette burn, but his left thigh has a big, dark mark. “I was really scared,” he says pointing to his groin. “But luckily everything was still there.”

The soldier retired from active service in 2003 to take up an administrative role for the previous military government in Gangaw Township, Magwe Region. In 2006, he officially retired from the Tatmadaw for another administrative role before being asked to stand for the USDP in the 2010 general election for a parliament in which 25 percent of the seats were reserved under the constitution for military appointees. That provision gives the army an effective veto on constitutional reform. Although he is clearly pro-military, U Hla Swe believes the Tatmadaw should gradually ease its grip on Myanmar’s parliament. “There are still many issues for the country to overcome, so the army should play a role in the country’s political future. In the 2015 election, the army has 25 percent of seats. In 2020, maybe 12 percent; after that seven percent. So I think it will gradually become less.”

Despite appearing to support a move away from the military’s powerful role, some of U Hla Swe’s opinions are conservative. He generated controversy in July 2015 for posting a series of homophobic outbursts on his Facebook page. And not surprisingly, he is unwilling to countenance any criticism of the Tatmadaw. “People in big towns, like Yangon and Mandalay, do not like the army, but they do not know what war is and have never needed the Tatmadaw. The people in villages, in contrary, support the army. Take for example Bago Yoma. The Tatmadaw and the Communist Party of Burma have been fighting there for decades, but now there is peace. Those people clearly like the army. They like to see the flag of Myanmar fly on top of the hill, that makes them happy.” The same goes, according to the Bullet, for the people in Kachin State. “The only Kachin who support the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) are living abroad.”

Did the Tatmadaw make a mistake when it savagely suppressed popular discontent during the national uprising in August 1988 and 3,000 people were slaughtered in cold blood? U Hla Swe has its own view on one of the most infamous examples of Tatmadaw brutality. “Now people say that the control in 1988 was bad, but this is false. A strong crackdown was needed to keep the country together. If the army had not controlled the crowds, our country would have been separated. We did the right thing.”

What about the brutal crackdown on protesters after a new generation of generals had seized power through a coup on September 18, 1988? Was that violence justified? “Both sides were very brutal. The army was using guns, but the people were chopping off heads. People were burnt alive or beheaded and their heads paraded on pikes. There was so much change and confusion at the time. The presidency changed hands three times in a matter of weeks. There were uprisings everywhere, so it was a good thing that the army took control strongly.”

He swapped the battlefield for

an office in the Union Parliament

in the capital Nay Pyi Taw.

Today, U Hla Swe has swapped the battlefield for an office in the Union parliament in Nay Pyi Taw, the capital that was secretly build and presented to the outside world in March 2006 (See box: The Seat of the Kings). “I used to think that people would never come here and that the generals who built it had no brains. But now, people are starting to come and I believe it will grow. Businessmen have recently begun buying land in the capital in anticipation of future growth.”

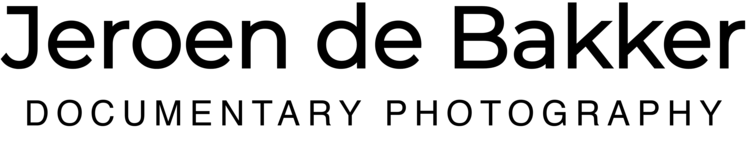

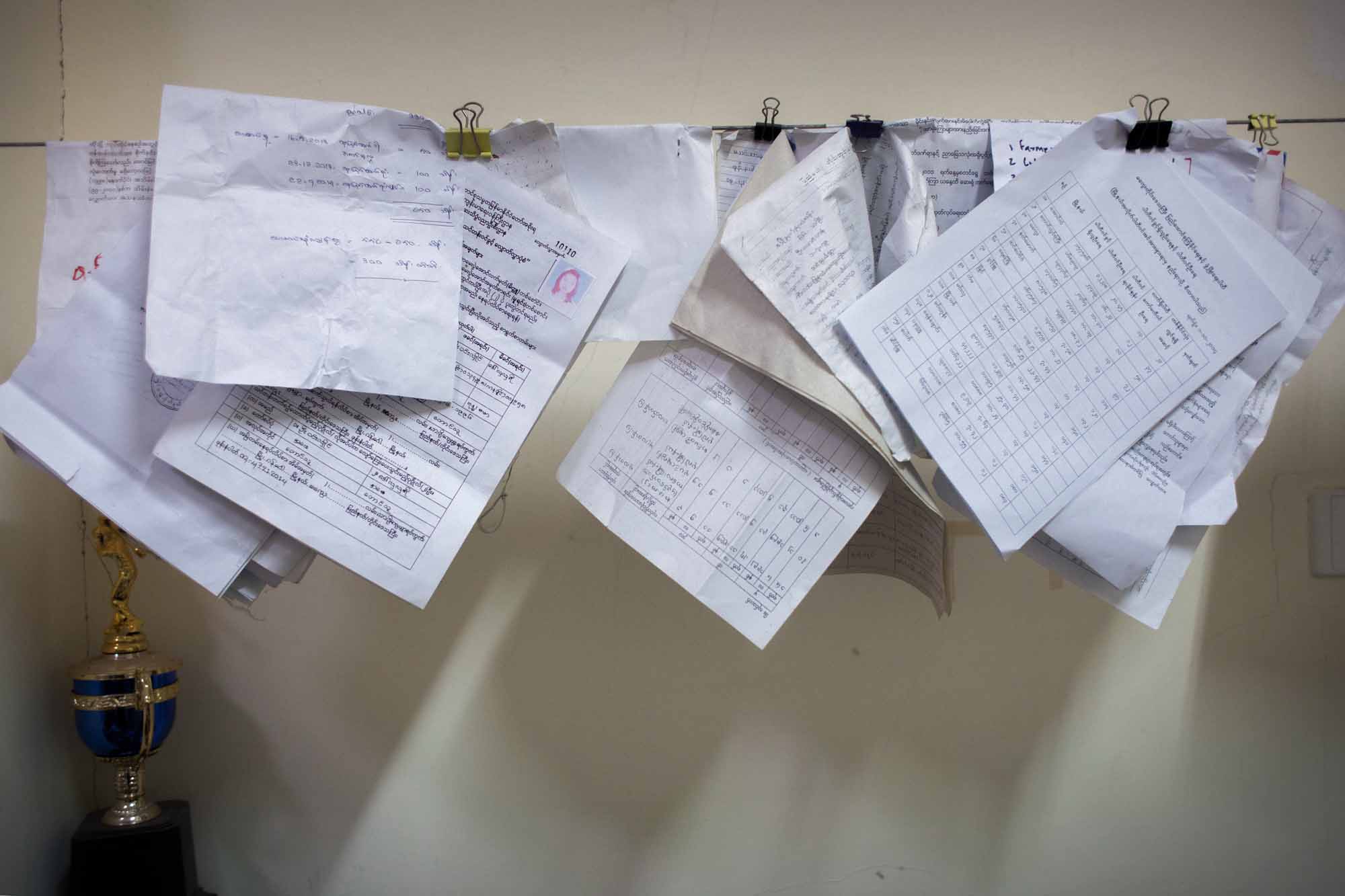

Nay Pyi Taw is hardly a buzzing metropolis, but there is more traffic on its roads than a few years ago and lively street-life is emerging in some areas. For U Hla Swe, the lack of congestion, 24-hour electricity and cheaper land makes living in Nay Pyi Taw far more desirable than Yangon. He spends about seven months a year in the capital, where he lives in a compound for USDP and USDP-aligned members of parliament. The compound is clean and spacious, unlike U Hla Swe’s room. It is has two beds. He sleeps in one and dumps stuff on the other: golf clubs, whisky bottles and paper documents. His desk is cluttered with paraphernalia and a clothesline in the room has tatty bits of paper clipped to it. “They remind me of all the work I have to do.” He spends little time in the room. “I leave for the parliament most mornings at about 6 or 7 and usually return until after dark.”

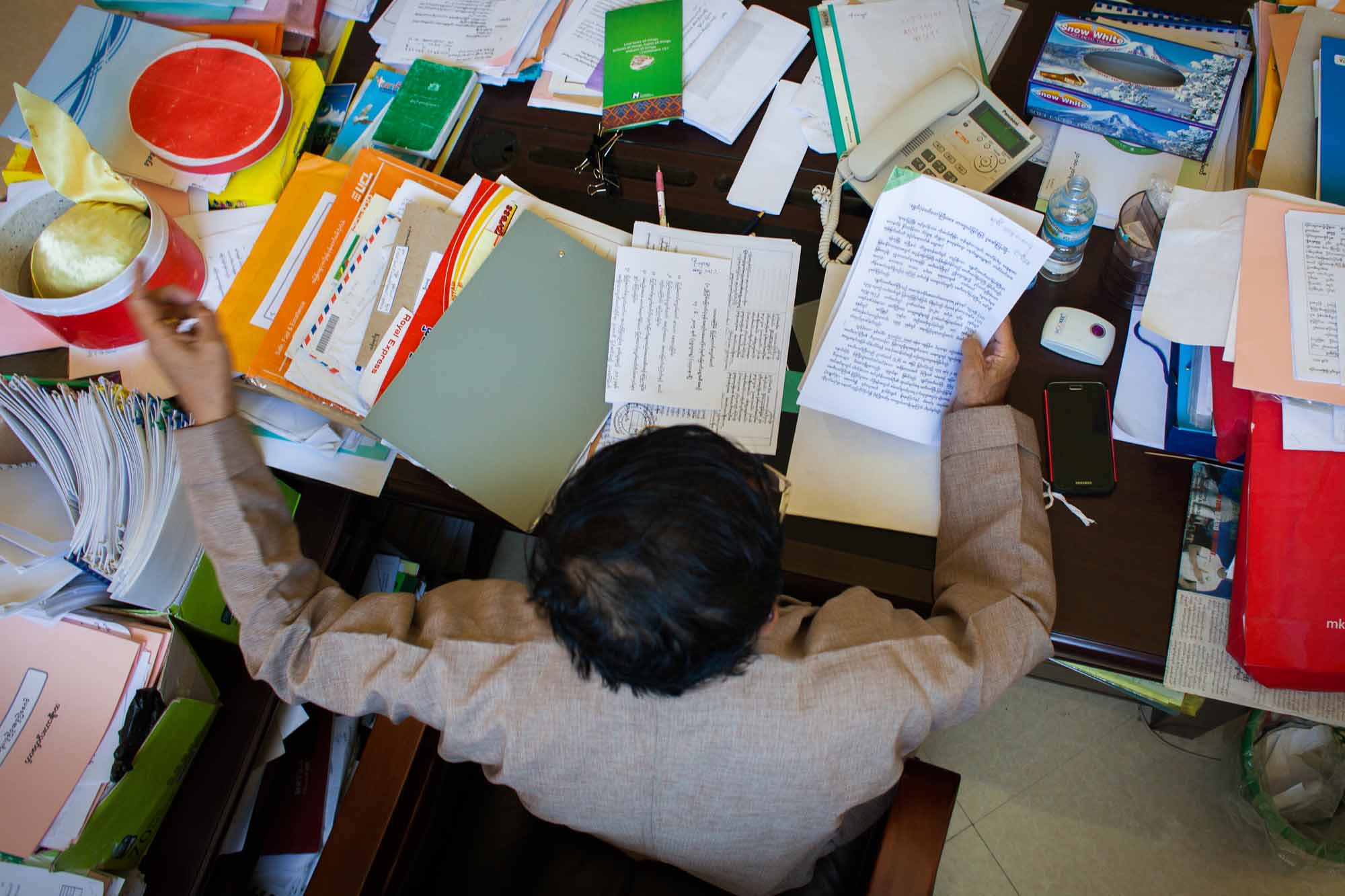

As his first term as a member of parliament comes to an end, does he intend to run for another term? “I think I am too old for politics. All our politicians are around 70, there needs to be a younger generation of politicians. But if my party wants me to run, I will run.” U Hla Swe can expect more competition if he decides to seek re-election because the 2010 general election was boycotted by the National League for Democracy. Five years on, can the USDP beat an opposition party that seems to enjoy widespread popularity? “The NLD and USDP are very close, so it is a big challenge.”

“I must admit it is a big challenge to move from a military government

to a democratic one.”

“We need to show that we are working for the people’s benefit. We have been building infrastructure such as roads and bridges, particularly in rural areas. That will help in the election.” U Hla Swe admits that it is a big challenge to move from a military government to a democratic one. “In the past, you could say ‘Mr. A, you go there, and Mr. B, you go there’, and they would do so. Now you say the same and they say ‘No, I don’t want to go there.’ That’s democracy. That’s good, we should not go back to the past.”

Nay Pyi Taw

The Seat of the Kings

It must be one of the strangest capitals in the world: Nay Pyi Taw, literally The Seat of the Kings, in central Myanmar, the heartland of Bamar culture. The military junta started building the new city from scratch and in secret in 2002, but why it decided to move the capital from Yangon to the dry plains, is a topic of much speculation, including its cost, which has been estimated at more than US$4 billion. Some say Senior General Than Shwe wanted to build his own capital, just like the old kings did. Others feel the generals genuinely feared a US invasion, and thought it wiser to build the new capital inland, far from the sea.

Whatever the rationale, on November 6 2005, the junta announced a mass relocation of civil servants to the new capital. The new inhabitants of Nay Pyi Taw entered a surreal world. Nay Pyi Taw is enormous: the city covers an area of over 7,000 square kilometre, almost five times the size of Greater London. The city’s buildings are grouped into zones that are far apart. Some say that the city is planned like this, because it would be harder to stage demonstrations in a city so large that walking is hardly possible. This would make it easier for the government to remain in control and avoid a repeat of the unrest in August 1988, when anarchy ruled for weeks in the former capital, Yangon.

Ten years on, many foreign embassies are refusing refusing to relocate to Nay Pyi Taw, partly because international schools are lacking there, and in part because Yangon is still the country’s commercial capital. But business people, who have to rely on connections, permissions and licenses have no other choice than to mingle with the bureaucrats in Nay Pyi Taw. Data from the 2014 census gives Nay Pyi Taw a population of more than 1 million, making it Myanmar’s third biggest city after Yangon and Mandalay. No one knows what will happen to Nay Pyi Taw when the democrats finally get to have their say in the country’s affairs. Will they opt for reinstating Yangon as the nation’s capital? Time will tell.