The smiling Octogenarian and his misunderstood disease

The smiling octogenarian

and his misunderstood disease

"I’m not naughty. You killed my doctor!"

By Oliver Slow

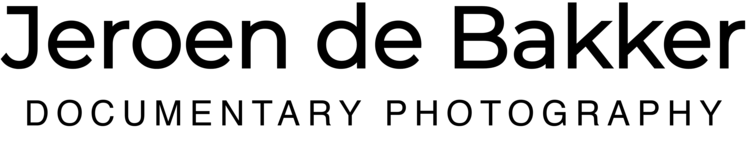

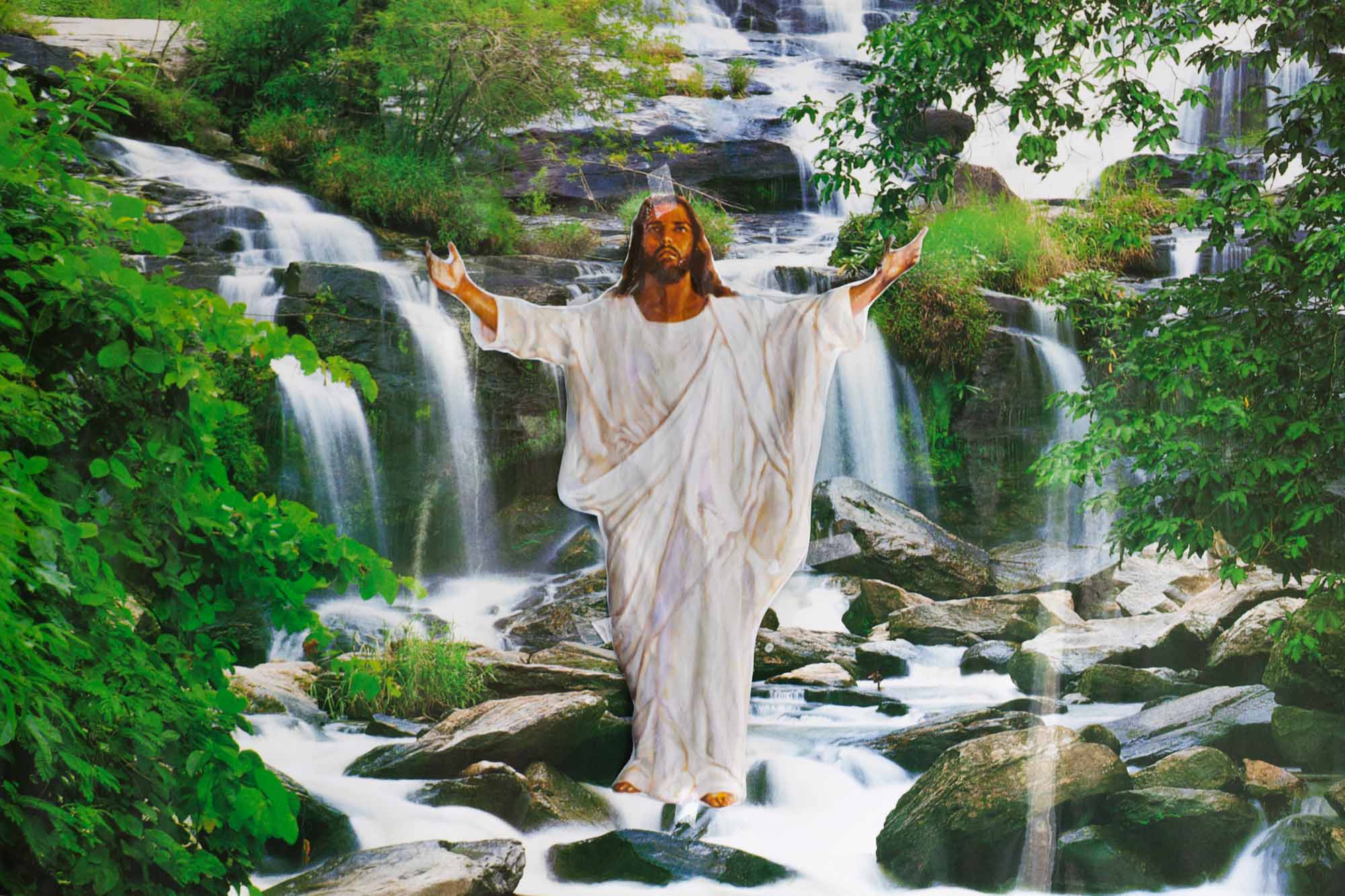

U Saw Silver, 89, wore a huge smile as he entered the small meeting room set aside for our interview at the Mawlamyine Christian Leprosy Hospital. He has long been cured of the leprosy he contracted in his teens, but the disease was diagnosed too late to prevent it causing permanent damage to his hands and feet, where the digits have almost entirely disappeared.

As U Saw Silver came into the room, I stood and greeted him with a firm handshake. The smile on his face grew wider. “Thank you,” he said, beaming. “Thank you for not finding my hands ugly. Some people think that my hands are horrible, but for my friends and family, it doesn’t matter.”

“Thank you for not finding

my hands ugly.”

Even though leprosy is one of the world’s oldest diseases, it is still greatly misunderstood. Leprosy – also known as Hansen’s Disease – is infectious and thought to be spread by close, frequent contact with an infected, untreated person. “It is the least contagious of all the communicable diseases,” said Dr. Saw Hsar Mu Lar, a leprosy specialist at the hospital. “It is very difficult to catch,” he said. “You have to spend a lot of time with somebody who is infected, and even then, not all leprosy patients can pass it on.”

A person who has been treated for leprosy is not contagious and most people have an immunity to the disease. In 2003, Myanmar reached the ‘elimination target’ set by the World Health Organisation (WHO), meaning that less than one in 10,000 inhabitants have the illness. Figures from the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations, citing WHO data, show that the number of new infections reported in Myanmar has hovered at about 3,000 for the past ten years.

The Mawlamyine hospital, founded by Christian missionaries in 1898, is on the southeastern outskirts of the Mon State capital. U Kyaw Zwar Oo moved to the area decades ago after his mother was admitted to the hospital. He runs a small shop opposite its entrance. “There was a time,” U Kyaw Zwar Oo remembers, “when people walking past the facility would often hold their noses, because they believed it would prevent them from being infected. That doesn’t happen anymore. Now people better understand the illness and the hospital has become an important part of the local community.”

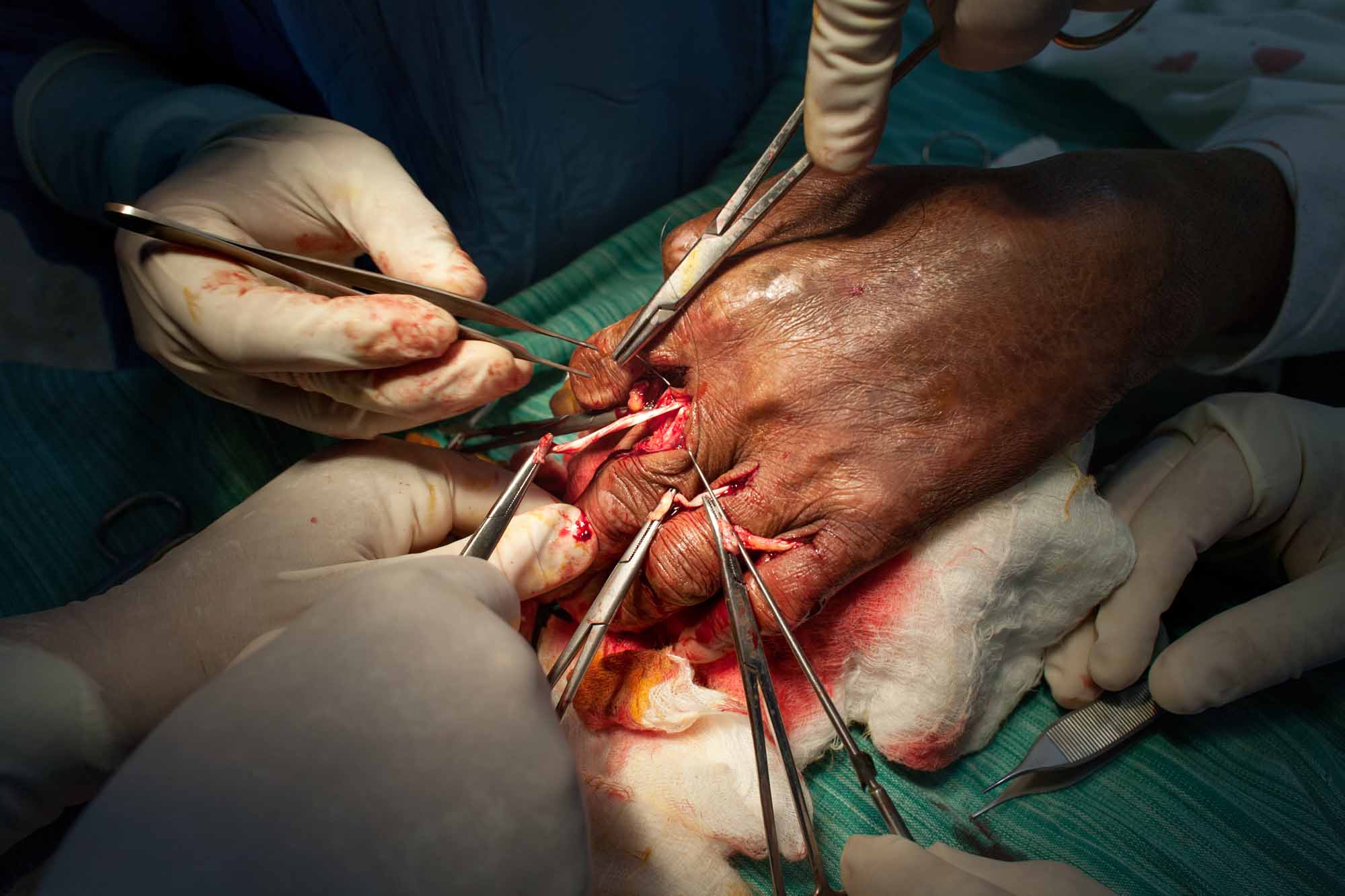

A disheartening challenge for those with leprosy, particularly those showing its disfiguring effects, is the stigma of being infected with a disease that is highly feared and little understood. “There is a strong belief in karma,” says Dr Zaw Moe Aung, country director for The Leprosy Mission Myanmar. “In Buddhism people believe that everything happens as a result of your deeds in the past. If you behaved badly in your past life, then you are ill in this life.”

Yet, leprosy can be cured at any time. Ma May Thet Khine, 14, lives across the Thanlwin River from Mawlamyine, on Bilu Island. A few months ago, her sister noticed blemishes on Ma May Thet Khine’s skin and took her to a doctor who immediately diagnosed leprosy. He referred the girl to the Mawlamyine hospital, where she is receiving treatment. “Ma May Thet Khine will make a full recovery,” Head nurse Daw Ni Ni Thein said. “She will be able to return to school within a few weeks.”

Back to U Saw Silver. As a young man, U Saw attended high school in Yangon’s Ahlone Township, in the shadow of the governor’s residence during the twilight years of British rule (1824 – 1948). He met the last two governors, Sir Archibald Douglas Cochrane and Sir Reginald Hugh Dorman-Smith. His memories of British rule are so strong he broke into a rendition of Rule Britannia during our conversation.

“When I saw the governor,” U Saw Silver said, “I would salute, but at one point I realised that it was more difficult for me to do that. That’s when I started to think that something was wrong with my hands. Back then doctors were unfamiliar with the disease so it took many more years before I was diagnosed.”

“My friend said I could be cured by a snake bite.

Either that, or it would kill me.”

After his mother died in 1949, a loss he still struggles to discuss, he moved in with an aunt’s family in a rural area north of Yangon. While playing in a field near his aunt’s house, a friend told him of a cure for his illness. “My friend, a devout Christian Karen, said I could be cured by a snake bite in my hand. Either that, or it would kill me. ‘It’s God’s will,’ he said.”

“My friend brought a snake from the field and gave it to me. I stood there for a while, looking at it, but the snake did nothing. So, I grabbed it by its neck and it bit me in my hand,” U Saw said, roaring with laughter when he thinks back to that bizarre moment 60 years ago. “The snake bit right through my hand, but its venom did not enter my skin. When I was standing there with this snake dangling on my hand, my aunt came out and killed the snake in one blow. She shouted at me: ‘Mr Silver, you’re so naughty!’ But I screamed back: “I’m not naughty. You killed my doctor!”

A few years after that incident, U Saw Silver heard about the hospital in Mawlamyine and, in 1953, travelled there by train from Yangon. “When I bought my ticket, I was told that I could not sit next to other travellers. I was made to travel in the back of the train. That really upset me at the time, but now I doesn’t bother me anymore.”

Although U Saw Silver no longer needs treatment, the hospital continues to play an important part in his life. He lives only a few minutes’ walk from the hospital compound, in a house he shared with his wife, also a leprosy patient, until she died seven years ago. Many of his children and grandchildren live nearby. “When I met my wife, I played football all the time. But my wife said to me, that I should choose between her and football. I looked at my sweetheart’s face, then I looked at my football, so lovely and round. But in the end, I chose my wife,” he said, with another fit of laughter.

U Saw Silver works as a leader of the community of leprosy patients and although it is something he never planned, he really enjoys the role. “I wanted to be a leader for Karen and Christian people, instead I am a leader of people who are affected by leprosy, of all races and religions. God didn’t give me what I want, he gave me what I need.”

3,000

new infections every year

Even though leprosy achieved the ‘elimination status’ set by the World Health Organisation in 2003, there are still an estimated 3.000 new cases of leprosy every year in Myanmar. Since 2007, the number of new cases has decreased slightly, from just over 3,600 to 3,000 in 2012. Many of the thousands of Myanmar who have been cured of leprosy have been permanently disabled by the disease.

Education has meant that knowledge of the disease has improved in Myanmar, but sufferers are still subjected to stigma in most parts of the country. As a predominantly Buddhist country, many Myanmar citizens believe in karma: the belief that if you are sick in this life, then you are paying for sins committed in a previous life. This belief can manifest strongly in a disease such as leprosy.

Despite some improvement in recent years, Myanmar’s healthcare budget has been one of the lowest in Southeast Asia. As a result, leprosy treatment has been overlooked in government allocations and philanthropic groups have assumed the responsibility of caring for those affected by the illness.

Myanmar has the most leprosy cases in the world, after India and Brazil. Between two and three million people worldwide have been permanently disabled because of leprosy.