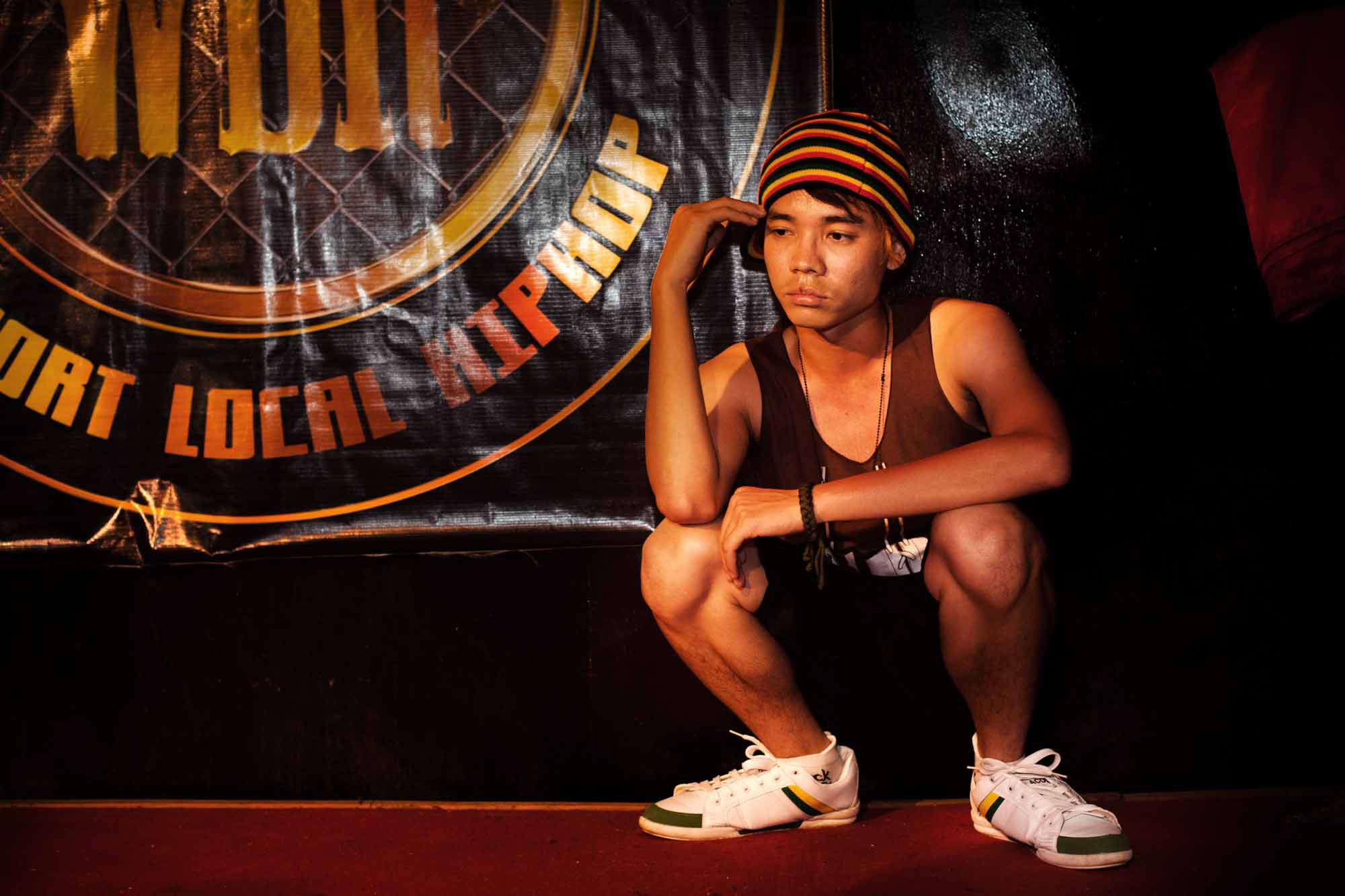

The Beat of Yangon

The Beat of Yangon

The rest of the world is slowly beginning to listen.

The question is: What will they hear?

Under a bridge in downtown Yangon, a few dozen young rappers gather for a late night jam session, leaping around the cracked pavement and rusty beams, flinging words into the air like shrapnel. One slaps a stencil against a pillar and spray paints it black, leaving the words “G-FAMILY” enshrined on the concrete. “We had to do that late at night and then run,” says Ye Yint with a laugh. He watches the action on a computer screen in his small apartment in downtown Yangon, where members of his group, One Way, are editing their latest promotional video.

Hip-hop in Myanmar is a story

of censorship, secret concerts and police beatings; of suppression,

youth and creative revolt.

One Way just released its debut album, but the group started rapping 13 years ago, when hip-hop was just beginning to echo through Myanmar. It’s a story of censorship, secret concerts and police beatings; of suppression, youth and creative revolt. Now the genre is finally coming into its own with a new generation of artists and fresh, original music – or mainstream swill, depending whom you ask. “The popular, mainstream tracks are basically all cheesy love songs,” says Ye Yint, while clicking through the computer screen’s landscape of simulated dials and meters as a pair of headstone-sized speakers fill the tiny room with his latest beat.

The space is where Ye Yint and his group compose and mix demo tracks, which they take to a professional sound studio to record. Their new album explores brotherhood, addiction, writer’s block and falling in love – real love, says Ye Yint, not cheesy clichés. The album’s title track, ‘Copies’, implores entertainers to quit ripping off each other’s music. “The song says that this album has its own sound, and that everybody should have their own original sound so other countries will see us and take us seriously,” Ye Yint says.

Underground

Original or not, the fact that Myanmar hip-hop has a mainstream at all is a big deal. Yan Yan Chan is a former member of the group ACID, one of Myanmar hip-hop’s founding fathers. When his career in music began, artists didn’t go underground to avoid selling out. They did it to avoid prison. “Back then hard rock was big,” says Yan Yan Chan. “People would go to rock concerts with huge rock stars, then they would leave and listen to rap at home,” he says, describing a community that began in the early ‘90s with impromptu jam sessions in public parks and under flyovers. One friend and future band mate had precious access to MTV through his father’s music store, and the teenagers would pirate Vanilla Ice and MC Hammer when they played the VHS tapes.

Yan Yan Chan said ACID made its first original tracks by recording the beats and lyrics separately on home recorders and then splicing them together. “Then we would find the guys who had their own cars and give them the cassette tapes and they would drive around playing it on the street. That’s how we got people to listen.”

One of these early fans was Ye Yint. He says legendary crooner Sai Sai Kham Waing was the first in Myanmar to experiment with hip-hop, but ACID made it big and made it like the American style of Dr Dre and the Notorious B.I.G. Then came Myanmar’s first generation of hip-hop artists: names such as Theory, Ng Ng and NS.

Old school

The beats were so raw and the lyrics aggressive; Myanmar people had never heard anything like it, says Yan Yan Chan. Neither had the government’s censors. The censorship board demanded manuscripts of songs written for voice and rhythm. A song did not have to touch on politics for the censors to reach for their red pen. Songs were rejected for their aggressive and informal tone or simply because they found some lyrics too strange. “One time the censorship board asked what ‘old school’ meant. We explained we were really saying ‘old screw,’ and it didn’t mean anything,” says Yan Yan Chan. “And they bought it.”

“One time the censorship board asked what ‘Old School’ meant.”

Other artists brandished their music for revolution, notably when monks were marching on the streets in 2007. The result was a witch hunt. ACID member Zeyar Thaw went to prison, but for his activist work with Generation Wave, not his music. Yet other artists were slandered, banned and arrested on stage for their lyrics and the censors deciphered anti-government messages in even the most innocent songs, forcing musicians to fight for every line.

One rapper was targeted for a tattoo on his back. “It was of a bald guy wearing Christian rosary beads on his wrist, but he looked sort of like a monk so the authorities thought it was a political statement,” Yan Yan Chan recalls. “He took off his shirt during a show and the police tried to haul him off the stage, but the crowd protested, so they let him go.”

Old ears, new beats

Ye Yint has his own censorship war stories, but he says these days there is nothing he is afraid to rap about. The government can blow smoke, but little else. Thus, a new generation of artists and fans is blooming. ACID is no more (Zeyar Thaw is now a member of parliament for the National League for Democracy), but Yan Yan Chan and other pioneers still record and perform beside recent breakouts, such as Snare, Mi Sandi and One Way, which headlined at the last Myanmar Music Awards. “The meaning behind it, it’s blunt. It’s a lot more real. It’s different,” says hip-hop impresario Bo San, referring to the elements of the genre that make it so fun and exciting for young urbanites – and so distasteful for many others.

Bo San, the founder of Bo Bo Entertainment, is one of Yangon’s biggest hip-hop producers and promoters. He organises shows and distributes music, including One Way’s new album. He argues that the music simply doesn’t fit well in a culture that has never been straightforward and aggressive, especially in small rural communities. But it’s not that those people can’t get used to the music, but that Myanmar’s unreliable infrastructure means only a few legends generate enough demand to justify distribution costs. “So who really knows if people in small towns would like One Way? There’s no real way to distribute One Way’s music there,” Bo San says.

The hip-hop industry can only support a select few superstars on their music alone. Most artists, such as Ye Yint, who quit a radio job to start One Way with two other DJs, support themselves as freelance rappers-for-hire for the rest of the hip-hop community, mixing tracks or composing beats for one another.

Nevertheless, demand is growing. Most of Bo Bo Entertainment’s record sales come from pop music, but its most profitable events and shows are hip-hop. New artists are beginning to experiment, fusing hip-hop with styles like K-pop and electronica to entice new fans. Expanding the gene pool may help to lift hip-hop from its status as a boutique genre.

ACID used similar tactics. Its first audiences had never seen heard that kind of singing, or every band singing at once, or their members leaping around the stage. There were jeers mixed with cheers, so the group tried splicing its tracks with classic Burmese pop songs. “People had never heard mixing before,” Yan Yan Chan says. “They would listen to the familiar chorus, then hear our rap come in, then pause for a moment, then applaud.” His take on the new mixes: “I guess I prefer the original style, but I guess all older guys say that.”

For Ye Yint, the newcomers are selling out their roots for kitschy mass market fare. One Way and other G-Family groups stay underground to make music on their terms, preserving a sound won in handcuffs and jail cells. He says the stakes are higher now that Myanmar’s music scene is attracting attention from overseas. “We’re catching the interest of producers in other countries, like Thailand and Vietnam. They’re interested that Myanmar musicians are putting their own music and lyrics out there. Not because they like our songs, but because our sound is there at all.” The rest of the world is slowly beginning to listen. The question is, what will they hear?

T-shirts and autographs

Ye Yint doesn’t make music for the market. Fans might hear One Way headline at the Myanmar Music Awards or in an impromptu jam session in the park; because they bought the group’s new album, or because someone passed them a mix of tracks cut in Ye Yint’s bedroom. He recalls a concert at the flower festival in Pyin Oo Lwin, the first time One Way had performed outside Yangon or Mandalay. Thousands of people showed up, wearing One Way T-shirts and pleading for autographs. “We didn't know people there had even heard our music. To see so many at that concert, we were shocked. It was an amazing experience.” Even though he is not making enough to be able to live off it, Ye Yint is a happy man. “I'm able to make my own music, music that stands on its own. And when people see me, they get excited because they love my music. That's what makes me happy.”